My father prefers fishing over hunting. It’s just more fun to be on a boat on the lake when the water is calmly reflecting the brilliant sun. Hunting, though? He technically can’t go anymore, but that doesn’t bother him. It’s probably been at least 30 years since he went and he doesn’t miss it. That doesn’t mean that he doesn’t appreciate it when a friend goes hunting and brings back a treat for him, though. I’m just putting that out there in case any of his friends are reading this.

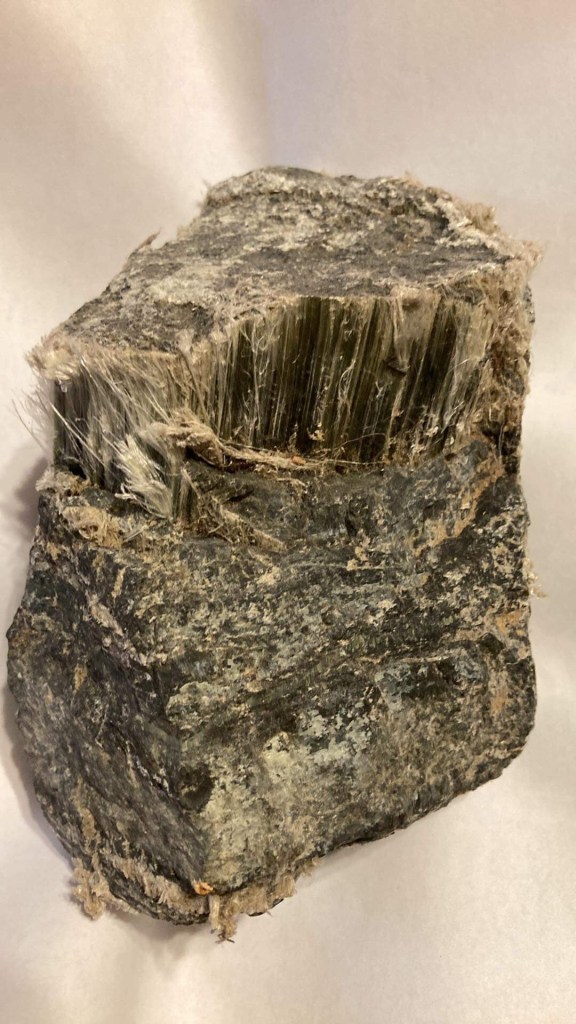

Today we set our scene in a townhouse in the late 1980s. Lunch time is coming up fast and my dad has been looking forward to the venison that his friend gave him. It is in the fridge wrapped in tinfoil. He opens the door and pulls the silver corners of the wrapping open and pulls a piece of meat out. He takes a bite.

Delicious. That’s what it is, deeeeelicious. He thinks to himself, Hey, you know who might like this? My five-year-old daughter.

There is really no way for him to know that I watched Bambi for the first time at Aunt Shirley’s house yesterday.

My father calls me over.

“Here, try some of this. You might like it.”

I look at the meat with interest. “What is it?”

“It’s deer meat,” he says.

I recoil and shake my head, frowning.

“Come on, it’s yummy,” he insists.

“No, I don’t want it.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t like deer meat.”

“How do you know if you don’t try it?”

I shake my head again.

My father is running out of convincing things to say. It’s time to pull out the big guns. It’s time to bust out his favourite Pink Floyd lyrics.

“If you don’t eat your meat, you can’t have any pudding,” he says.

I stare at him. Tears are beginning to form in my eyes.

My dad puts on a silly accent and says, “How can you have any puuuudinnggg if you don’t eat your meat?”

That’s when I burst out with, “I don’t want to eat Bambi’s mom!” The tears are rolling down my cheeks and my eyes are glistening as I look up at him.

This is a plot twist that my father was not expecting. He quietly wraps the deer meat up in the tinfoil and puts it back in the fridge.